My interest in resilience began earlier than I realised. As someone with a high ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) score, the first in my family to attend university, and having experienced multiple recessions in a single-parent household, I was convinced that ACEs are not a crystal ball…experiencing them doesn’t predict the future.

More than an ACE score

As a post-16 teacher, I saw many ‘high ACE scorers’ return to education and become teachers, nurses, social workers, and lawyers. I wondered why the focus was often on ACEs and not protective factors. My doctoral thesis aimed to listen to the stories of resilience from those who had left and then returned to education (Borrett, 2019; Borrett & Rowley, 2020). The research revealed not just stories of resilience but also transformational moments and adversarial growth.

Listening to stories

Through my research, I began to understand the process that returners to education had undergone and the protective mechanisms that enabled their transformation. These learners used a gap in their education as a period of reflection, viewing overcoming their adversities as unique strengths, capabilities, and resources. This renewed perspective enabled them to return to education successfully. They didn’t just bounce back; they propelled forward.

Developing a resilience programme

I began to wonder if I could unpick this process and apply it to other learners struggling to engage so they could continue with formal learning without needing to take a break. I was fortunate to work with colleges in eastern England that requested a programme echoing my research findings. I began developing a programme based on the protective mechanisms identified in my research. This came to be known as the Resilience Support Teaching Assistants (RESTA) programme.

Initially, I worked with small groups of students in colleges, and the programme showed promising signs, particularly increased scores on the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) and the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWS). Unfortunately, the COVID pandemic paused the programme.

When colleges returned post-pandemic, they reported having too many students to refer to the programme and asked if it could be adapted for them to run it themselves. Around the same time, a former colleague, Dr. Jemma Carter, was working on her Applied Trauma Responsive Classroom Model (ATRCM) (Carter, 2023). Through discussion with Dr Carter, it became clear that any programme would need to be sequential and developmentally appropriate in order for young people to feel the safety and belonging needed to build protective mechanisms (Carter & Borrett, 2023). This led to further action research developing the programme.

The RESTA programme

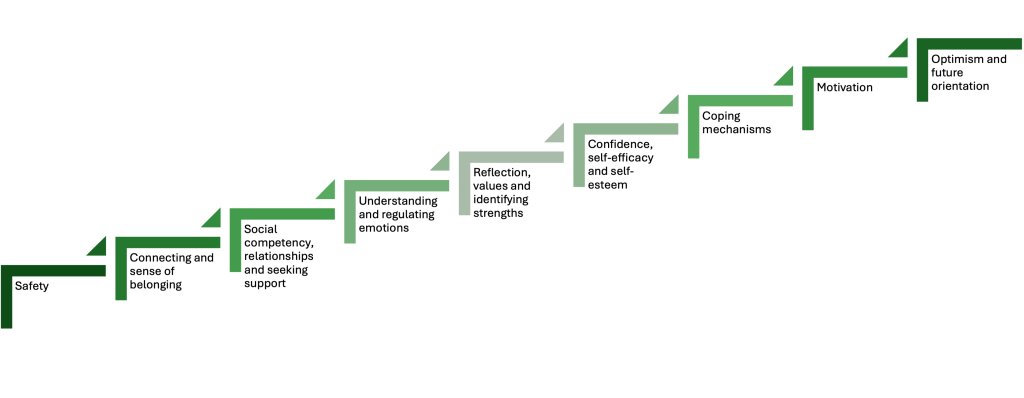

The RESTA programme is focused on building connections and encourages a sense of belonging before working on understanding emotions, values, and accessing motivation to bounce back when a challenge arises. RESTA prioritises the change that can come from within and highlights the value of reflection in activating student strengths.

Initial RESTA training takes 6 days and is followed up by skills workshops and supervision from EPs.

Action research for the RESTA programme

In the first stage of the action research project, I worked with colleges to develop the programme. Each teacher was trained on different parts of the programme, reviewed it for ease of understanding, and provided feedback. Teachers from different levels within the college adapted resources for the various levels. They ran the sessions and reported back, with students helping design some resources and activities.

Once confident the programme could be delivered by staff, I ran a second pilot to train RESTA practitioners. This stage included both post-16 and secondary school staff.

The research confirmed the original programme’s findings, with increases on the Brief Resiliency Scale and anecdotal evidence of students reengaging and increasing attendance. However, the RESTAs noted difficulties with settings understanding the programme. They wanted their settings to understand resilience principles so that any work carried out in sessions continued in the classroom. I also noted that individual/small group intervention did not adequately address the system’s role in developing protective mechanisms.

In the final stage, we explored whether a whole-school approach alongside the programme would lead to better outcomes. Educational Psychologists (EPs), teachers, and senior leaders worked with the RESTAs to develop principles that would embed resilience throughout the system and ensure the RESTAs’ work was integrated into everyday practice. At the request of schools and colleges, we developed this into a quality mark to demonstrate each organisation’s efforts.

RESTAs take a strengths-based, relational approach

At its heart, the RESTA programme is positive and proactive. The influence of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems theory (1979) means that it acknowledges the role all system members play in developing resilience and rejects the idea that resilience is a trait. The underpinning values of positive psychology focus on activating existing strengths, resources, and capabilities.

A relational approach ensuring safety, connection, and belonging (as per the ATRCM) is key. With this solid foundation, students can appraise and reflect to make the changes needed to activate their strengths. RESTAs work sequentially through the programme, moving students from an initial place of safety to future thinking. RESTAs have a range of psychoeducation activities and resources and are supervised by EPs.

The value of the EP in supporting systems

For me, the RESTA programme represents a shift in thinking that recognises both the role of the system and the importance of focusing on what is working well. Schools and colleges are now holding hope for young people who have experienced adversity, empowering them to support change. Throughout its development, the programme has been driven by the needs of colleges and schools, with young people’s voices being fundamental to its development. It demonstrates the value of collaboration between EPs and post-16 systems, highlighting the capability of EPs to bring about systemic and organisational change.

References

Borrett, E (2019) Using Visual and Participatory Research Methods to Describe Processes of Educational Resilience in Returners to Education. Prof Doc Thesis University of East London School of Psychology https://doi.org/10.15123/uel.883qz

Borrett, E., & Rowley, J. (2020). Using visual and participatory research methods to describe processes of educational resilience in returners to education. Educational and Child Psychology, 37 (3). https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2020.37.3.10

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Carter, J. (2023). Trauma informed care and the Applied Trauma Responsive Classroom Model (ATRCM). Assessment and Development Matters, 15 (4). https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsadm.2023.15.4.14

Carter, J. and Borrett, E. (2023). Considering Ways to Operationalise Trauma-Informed Practice for Education Settings. Educational Psychology Research and Practice, 9 (1), pp. 1-7. https://doi.org/10.15123/uel.8wqx9