Supporting neurodivergent young people during the transition to adulthood: A case study.

Research suggests that for neurodivergent young people, the transition to adulthood is fraught with challenge and anxiety (Crompton & Bond, 2022; Roux, 2015).

In this long reader, I will introduce why this is the case and provide a descriptive case study of a setting offering support for neurodivergent young people. I will end by providing key points to consider when setting up similar support in other settings.

Outcomes

This group of young people are less likely to enrol in or finish higher education, less likely to have a stable, well-paid job, have less social support and are, unsurprisingly, more likely to struggle with their mental health (Newman et al., 2011; Kuriyan et al., 2013; Gordon & Fabiano, 2019).

It is important to note that these vulnerabilities appear to apply to neurodivergent young people regardless of specific skills, with autistic young people being particularly vulnerable (Newman et al., 2011; Orsmund et al., 2013). This could be related to difficulties associated with various types of neurodivergence, such as difficulties with abstract thinking affecting future planning (Wong et al., 2020) and difficulties with executive functioning skills (Almeda & Asbell-Clark, 2021). However, when looking at the problem through a social model of disability, the neurotypical expectations and environment they are faced with also present a significant challenge for these young people.

Experiences of the transition to adulthood

My systematic literature review, which developed a biopsychosocial ecosystemic model of the transition to adulthood (Crompton & Bond, 2022), suggested that this is a time associated with significant anxiety for parents and professionals and well as young people. There is a strong desire to help, but both parents and school staff are constrained by various barriers:

- a lack of knowledge

- lack of time/money

- difficult relationships

- a lack of confidence.

At a societal level, there is still significant stigma present, which, alongside traditional expectations of ‘success’ around education and employment, place additional pressure on young people. A notable absence from the literature was friendships and peers, an important source of support for many neurotypical young people.

Supporting the transition

Research suggests that accessing transition support leads to more positive outcomes (Hagner et al., 2012). Young people in the UK who have an education, health and care plan (EHCP) have a statutory entitlement to transition support, beginning at age 13-14 (DfE, 2015). However, there are many neurodivergent young people who do not have EHCPs and this group often receive little to no transition support.

There are significant ongoing concerns in the UK around the pressures on schools, particularly regarding special educational needs, with limited resources and overworking commonplace (DfE, 2022; Sellen, (2016).

St Matthews*: A case study

St Matthews is a sixth form in the North of England. My involvement with St Matthews came from their involvement in a pilot for a newly developed transition support planning template (GMAC, 2020), this developed into a thesis research study looking at St Matthews support programme to establish what good support looks like and what the facilitators and barriers to implementation might be. St Matthews are keen to share their programme and experience to improve experiences for other young people.

The support programme was aimed at neurodivergent young people who did not have an Education, health and care plan and therefore had no statutory entitlement to support. It was run by Anna, the school’s support and wellbeing officer. St Matthews’ transition support programme included:

- An initial session with a key member of staff and use the transition planning template to identify needs and set goals.

- Drop-in sessions to talk through difficulties or worries.

- A six week psycho-educative programme to support young people develop skills highlighted from the template such as, emotions, friendships, hygiene, organisation, transport and sleep.

- Peer support through a weekly ‘Neurodiversity group’. Awareness and stigma reduction campaigns were carried out as part of the group’s role.

- Support sessions focused on the transition to university.

Young people could self-refer to the programme or were identified by teachers/parents as being vulnerable during the transition. No diagnosis was required, only self-identification as neurodivergent. The cohort were predominantly female (60%) and autistic (60%), although young people with a variety of diagnoses were involved. Self-identification may have led to some bias towards groups more likely to seek help (Mandy, 2019).

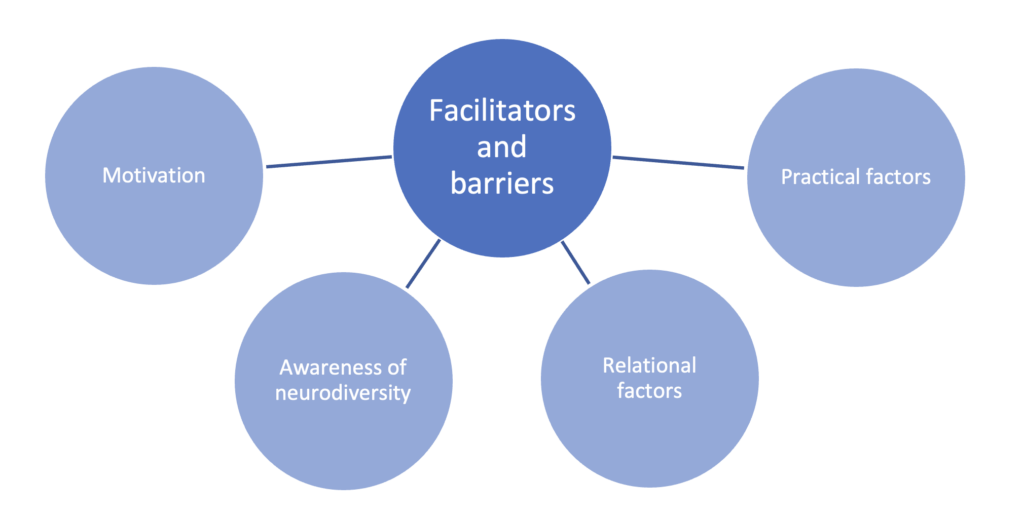

I gathered data through interviews and focus groups with young people, parents and school staff which I then analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (2019) reflexive thematic analysis, with consideration given to contextual data from policies, documents and observations gained during research visits. I identified four themes around the facilitators and barriers to implementing transition support for neurodivergent young people:

- motivation

- awareness of neurodiversity

- relational factors

- practical factors.

Motivation

‘everyone who’s sat in this room is doing a job but actually what they’re doing is also going above and beyond …. their role in college but they’re taking it to another level’

There was a need for school staff to be motivated in order to develop and run the support programme, Anna, who was in charge of the project served as a driving force. Personal motivation, at times, came from lived experience. It was important that the motivation stretched to senior members of the school team in order to provide systemic support.

Motivating young people to engage with support could be challenging, as the topic could often trigger anxiety. The transition template’s clear structure appeared supportive in reducing anxiety and encouraging the development of clear goals. Having clear ambitions was a facilitative factor, but finding ambitions was difficult for many, with a lot of uncertainty present about what young people wanted to achieve in adulthood. Wong et al. (2020) suggest that providing concrete examples and role models may be supportive in identifying career aspirations.

Awareness of neurodiversity

‘Whoever comes in here or goes to the group they seem to just bond don’t they even if they’re so different but a lot of them do have ADHD or autism and they do talk about it … normalising it is a big thing cos we’re more aware we can talk about it with them’

Ambitions to reduce stigma and increase inclusivity were in keeping with the school ethos. A sense of belonging is key to wellbeing (Maslow, 1954). The neurodiversity group was felt to provide an inclusive atmosphere where young people could access social support and feel accepted.

It was important for young people that transition support felt inclusive and recognised the full range of their experiences, particularly around LGBTQ+ issues, as it is more common for neurodivergent young people to identify as LGBTQ+ (Hillier et al., 2020).

Relational factors

‘easier to speak to people you don’t have to worry as much…because you can’t get it wrong…I feel like I can say what I think… I find it difficult usually cos I don’t know if people understand’

Relationships were vital to the programme’s success. Positive, trusting relationships offered a source of support and safety, which was valued. Young people highlighted having a space to be listened to and being accepted for who they were. Positive relationships allowed staff to challenge young people and confront more difficult topics, such as sexuality or hygiene.

Relationships with parents enabled support to be provided to families, building capacity, and allowed staff to gain information about young people’s needs.

This is consistent with the literature in reinforcing the importance of collaboration between all stakeholders (Hetherington et al., 2010; Kohler et al., 2016).

Practical factors

There was clear systemic support for the programme which facilitated its implementation. Key members of staff responsible for the project were supported by senior management, enabling the resourcing and prioritisation of the programme.

The school had recently received comprehensive training update focused around neurodiversity, including training on autism, ADHD and executive functioning. This generated momentum and increased the confidence of staff members, a common barrier to offering support (Crompton & Bond, 2022).

Practical factors identified as barriers included: lack of consistent room or consistent rules, individual timetabling clashes, lack of knowledge about what support was available and a desire for privacy.

While some found it helpful, the transition template was demotivating to many. It was viewed as too long and large sections were irrelevant to many of the high achieving young people involved.

Good quality, valued support is possible, despite systemic barriers

Neurodivergent young people appear to benefit from transition support, although further research could look at whether support improves long-term outcomes. While there are systemic barriers to offering support to more neurodivergent young people, it is possible to realise a quality and evidence-informed programme.

Those looking to implement support programmes should:

- Consider systemic influences and ensure buy-in is present at a high level within the school

- Think about the practicalities and how to ensure accessibility

- Ensure staff are knowledgeable and confident

- Consider the overall ethos and priorities of the school, to ensure inclusivity is present outside the programme

- Include reference to issues of developmental importance, such as sexuality and relationships, identity and aspirations

*pseudonyms are used throughout this blog

References

Almeda, M.V., Asbell-Clarke, J. (2021). Scaffolding Executive Function in Game-Based Learning to Improve Productive Persistence and Computational Thinking in Neurodiverse Learners. In: Fang, X. (eds) HCI in Games: Serious and Immersive Games. HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science[CB2] , vol 12790. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77414-1_12

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health, 11(4), 589-597. DOI: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Crompton, R.J. & Bond, C. (2022), The experience of transitioning to adulthood for young people on the autistic spectrum in the UK: a framework synthesis of current evidence using an Ecosystemic model. J Res Spec Educ Needs, 22, 309-322. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12569

Department for Education and Department of Health (2015) Special educational needs and disability CoP: 0 to 25 years. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-code-of-practice-0-to-25 (Accessed: 6/4/2021).

Department for Education and Department of Health (2022) SEND and AP Green Paper. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-and-ap-green-paper-responding-to-the-consultation (accessed 29/11/22)

Greater Manchester Autism Consortium (2020) Greater Manchester Transition Checklist. Available at https://www.autismgm.org.uk/transitions-resources

Gordon, C.T. & Fabiano, G.A. (2019) The Transition of Youth with ADHD into the Workforce: Review and Future Directions. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev, 22, 316–347 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00274-4

Hagner, D., Kurtz, A., Cloutier, H., Arakelian, C., Brucker, D., & May, J. (2012) Outcomes of family-centered transition process for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and other Developmental Disabilities, 27 (1), 42-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357611430841

Hetherington, S. A., Durant-Jones, L., Johnson, K., Nolan, K., Smith, E., Taylor-Brown, S., & Tuttle, J. (2010) The lived experiences of adolescents with disabilities and their parents in transition planning. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25 (3), 163-172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357610373760

Hillier, A., Gallop, N., Mendes, E., Tellez, D., Buckingham, A., Nizami, A., & Otoole, D. (2020). LGBTQ+ and autism spectrum disorder: Experiences and challenges. International journal of transgender health, 21(1), 98-110. DOI: 10.1080/15532739.2019.1594484

Kohler, P., Gothberg, J., Fowler, C &, Coyle, J. (2016) Taxonomy for transition programming 2.0: A model for planning, organizing, and evaluating transition education, services, and programmes. Retrieved from: https://transitionta.org/sites/default/files/Tax_Trans_Prog_0.pdf

Kuriyan, A. B., Pelham, W. E., Molina, B. S., Waschbusch, D. A., Gnagy, E. M., Sibley, M. H., … & Kent, K. M. (2013). Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 41(1), 27-41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9658-z

Mandy, W. (2019). Social camouflaging in autism: Is it time to lose the mask? Autism, 23(8), 1879–1881. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319878559

Maslow, A. H. (1954). The instinctoid nature of basic needs. Journal of personality.

Newman, L., Wager, M., Knokey, A. M., Marder, C., Nagle, K., Shaver, D., … & Schwarting, M. (2011) The post high-school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school. A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) Retrieved from: eric.ed.gov/?id=ED524044 on 6/4/2021

Orsmund, G., Shattuck, P., Cooper, B., Sterzing, P., & Anderson, K. (2013) Social Participation Among Young Adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2710-2719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1833-8

Roux, A. (2015) Falling off the services cliff. Accessed from: https://drexel.edu/autismoutcomes/blog/overview/2015/August/falling-off-the-services-cliff/ on 8/1/2020

Sellen, P. (2016) Teacher workload and professional development in England’s secondary schools: Insights from TALIS. Education Policy Institute. Accessed on 28/5/2021 from: TeacherWorkload_EPI.pdf (teachertoolkit.co.uk)

Wong, J., Cohn, E., Coster, W., & Orsmond, G. (2020) “Success doesn’t happen in the traditional way”: Experiences of school personnel who provide employment preparation for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 77 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101631