Mia (not her real name) is fourteen and she and I are sitting in a small intervention room off one of the main corridors in the high school she attends.

She is popular and involved in everything at school but I’ve been asked to see her because she has disclosed self-harm. We’ve met each other a couple of times now so the initial nerves on both sides have settled down and I’m now going to see if she is willing to try something radically different from the things she’s tried before to deal with her distressing thoughts.

Simon: So this thought about hurting others in your class has been pushing you around for how long now?

Mia: Since Year Eight

Simon: And you’ve been trying all sorts of things to get rid of it like thinking positively…distracting yourself?

Mia: Yeah but nothing works.

Simon: OK so nothing makes the thought go away. Do you think you’d be up for trying something different? Something that doesn’t get rid of the thought but maybe makes it less bothersome?

Mia: OK

Simon: Well what I’d like you to do is to take the thought and sing it to the tune of Happy Birthday.

Mia (laughing): That’s weird!

Mia is right, by any stretch of the imagination it is a weird thing to ask a fourteen-year-old to do…so why am I asking her to do it? The answer relates to my own personal experience of anxiety and a recent reformulation of cognitive behavioural techniques called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Like Mia I get anxious thoughts and I believe my interest in CBT has been fuelled, in part, by my desire to learn how to cope with them better. Over the past 10 years I have assiduously completed thought records, uncovered cognitive biases and looked for evidence to challenge my thinking all with the aim of reducing my anxiety but when I stand up in front of a group of people to talk about CBT I still get intrusive, anxious thoughts. After all the effort I’ve put in I’d hoped to have cracked the anxiety problem by now but the thoughts always come back whatever technique I try and I had assumed that I just wasn’t doing it right or with enough conviction. But what if it was a fight I couldn’t win? What if my struggle against anxious thoughts has been making my problems worse rather than better? This is the position at the heart of ACT and has resulted in a fundamental shift in the way many CBT therapists work with young people’s distressing thoughts.

Struggling with Thoughts

A great deal of research has been carried out into the nature of this struggle with thoughts. An early example by Purdon and Clark (1992) surveyed 293 students, none of whom had a diagnosed mental health problem, regarding the presence or absence of intrusive thoughts. The results showed that intrusive thoughts, far from being unusual and only present for people with mental health problems, were widespread and essentially a normal phenomena in healthy individuals.

| ‘Intrusive’ thought | Female % | Male % |

| Hitting animals or people with car | 46 | 54 |

| Swerving into traffic | 55 | 52 |

| Fatally pushing friend | 9 | 22 |

| Insulting authority figure | 34 | 48 |

| Wrecking something | 32 | 33 |

| Contamination from doors | 35 | 24 |

Table 1. Selected items from Purdon C. & Clark D (1992) demonstrating the percentages of students reporting intrusive thoughts.

In addition, psychologists Richard McNally and Joseph Ricardi have demonstrated that if you attempt to suppress such thoughts it might work in the short term but as soon as you stop actively suppressing them they are three times more likely to return.

Language: tool, trap or both?

So why might this the case? Researchers into Relational Frame Theory (RFT), the behavioural science upon which ACT is based, argue that the inability to get rid of unwanted thoughts is a consequence of the human capacity for language itself. RFT argues that human language enables human beings to go beyond responding solely to the physical characteristics of objects to the relationships between them. For example not only can you perceive that a ball is round and bouncy, you are also aware when holding a golf ball and a tennis ball that the latter is bigger. The concept of bigger is not an attribute of the tennis ball itself and your answer to which is bigger changes with the context so if I now give you a tennis ball and a basketball you easily perceive that the basketball is now bigger. And this capacity is not just limited to balls. You can generalise the concept of bigger to a range of other stimuli without further instruction.

This is a uniquely human capacity and it is not something we can turn on or off. We are locked into perceiving the relationships between things: big/small, same/different, past/future, good/bad, etc. One of the most basic relationships we learn between stimuli is ‘opposites’, so when we have the thought “I’m nice person” in our heads the thought “I’m a nasty person” can be triggered too. This is why trying to replace or challenge negative thoughts doesn’t really work, as the more we try to not have a particular thought, the more we will have it.

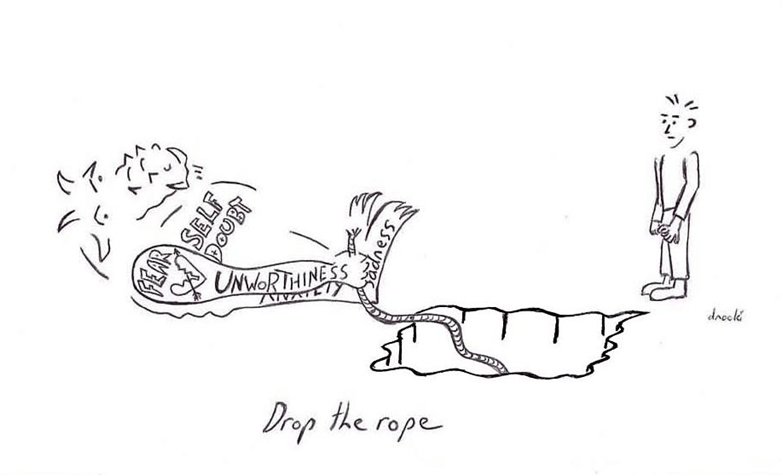

In ACT this struggle with our thoughts is likened to a tug-of-war with a monster. We struggle against this monster by pulling on the rope but all we end up doing is exhausting ourselves with the effort and putting our lives on hold. In ACT we encourage young people to “drop the rope”. This does not mean “giving up” but rather accepting the presence of anxious thoughts and feelings at challenging times and re-engaging with a life they value.

In my own life I have found this position liberating. I know that as I approach any challenging situation, like standing up in front of a group of people to talk about CBT, a whole range of difficult thoughts will come into my head – and this is normal! I can do very little to prevent these thoughts from turning up but I can stop struggling with them and free my time and energy up to concentrate on the job in hand.

In my work with Mia I spent the first two sessions developing the beginnings of this accepting position. I’ve asked her about the nature of her distressing thoughts without judging or attempting to change them and then explored what she has tried over time to get rid of them. So far we have arrived at the position of “nothing works” and counter-intuitively this is exactly where I need her to be. I need her to be ready to explore the idea that control of thinking is the problem not the solution.

And this is where singing Happy Birthday comes in. Instead of trying to change or get rid of her thoughts, I want Mia to develop a new relationship with them. I want her to see her thoughts not as a threat to be eliminated but as merely words or a collection of sounds. Oh and also I’m hoping to raise a laugh about it too.

Simon (smiling): You’re right it is weird isn’t it? Are you willing to give it a go in spite of the fact your mind is telling you it’s weird? I’ll sing it with you if that will help?

Mia: Yeah that would help.

Simon & Mia (singing): I feel like hurting them, I feel like hurting them, I feeeeel like hurting them, I feel like hurting them.

Simon: Has anything happened to the thought?

Mia (smiling): Yeah. It’s still there but it doesn’t seem so big.

Simon: Less bothersome?

Mia: Right.

Further reading

Harris, R. (2009) ACT Made Simple: a quick start guide to ACT basics and beyond. New Harbinger Publications Inc.

Hayes, L..L., Ciarrochi, J. (2015) The Thriving Adolescent: Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Positive Psychology to Help Teens Manage Emotions, Achieve Goals, and Build Connection. New Harbinger Publications Inc.

Hayes, L..L., Ciarrochi, J. & Bailey, A (2015) Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life for Teens: A Guide to Living an Extraordinary Life. New Harbinger Publications Inc.

Jackson Brown, F. & Gillard, D. (2016). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Dummies. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.