When the pandemic first hit, I, like most mental health researchers, was extremely concerned about how it could impact the mental health of children and young people (CYP).

The early days of the pandemic

This was uncharted territory, and we couldn’t ignore the potential for detrimental consequences for children and young people, especially those who had pre-existing mental health difficulties or for whom home is not a safe place.

In those first days, academic journals were filled with editorials expressing these concerns. Gradually, empirical evidence started to show that, on average, CYP’s mental health had declined. For its part, mainstream media was rife with headlines about a ‘mental health crisis’ among CYP.

Meanwhile, as our team worked with CYP and their families to monitor the impacts of the pandemic, we started to hear a different message: some CYP were seeing mental health improvements during lockdown. This was a group that was not making the headlines, yet it was more than just an isolated case here and there. In fact, many families were telling us that they were coping better during lockdown.

The research

So what was actually happening?

Our team of researchers at Oxford and Cambridge set out to study this group more systematically. At that point, we had collected lots of anecdotal evidence, but we wanted to learn more about the numbers. How many children and young people had better mental health during the pandemic? And why?

We began by running a consultation survey with CYP and parents who perceived mental health improvements during this time. We had hoped to get responses from around 50 or so people to help inform our research… instead we got 400. Clearly improvement was not an uncommon experience.

These 400 respondents (approx. 100 CYP and 300 parents) gave a wide range of reasons about why they thought they/their child had had better mental health during lockdown. Many talked about school, specifically that being away from the physical school environment meant they experienced less stress and pressure and could learn in a way that suited them best. Others suggested that relationships with friends and family improved, especially with more time to devote to these relationships. Still others talked about how their pre-existing mental health needs were better met at home.

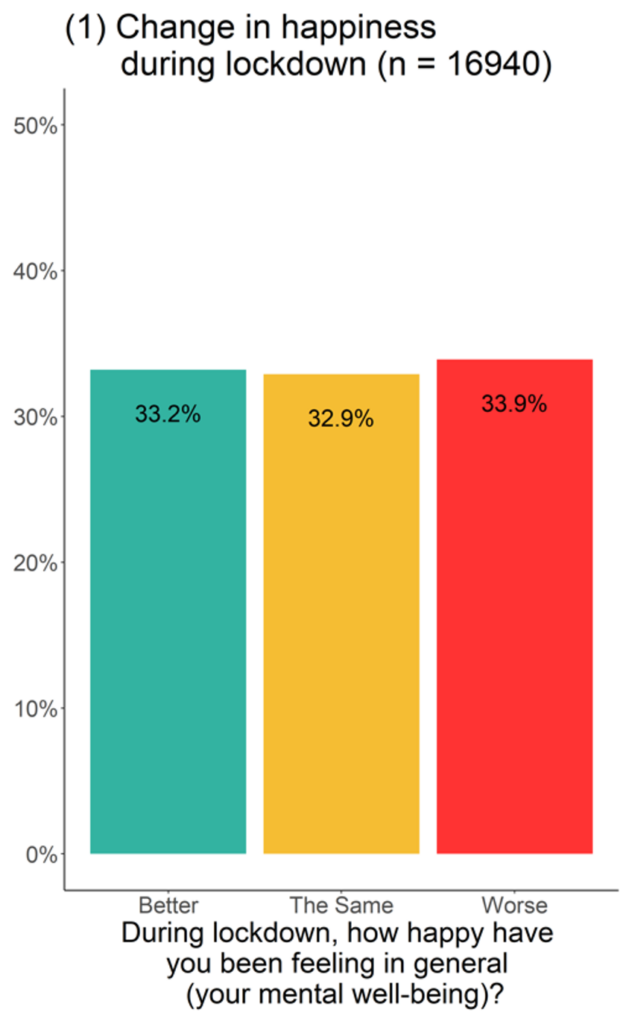

We used these ideas to design an analysis of data from the OxWell Student Survey, a large survey of English primary and secondary school pupils. In May-July 2020, the survey asked pupils to share their experiences of the pandemic, including changes in their mental wellbeing, school experiences, and relationships. The survey, which was completed by nearly 17,000 pupils, provided an excellent opportunity to learn at scale about the group who had fared better during lockdown.

The key findings

When we first looked at the results, even I was shocked. One in three pupils reported that their mental wellbeing had improved during lockdown! Another third reported that their mental wellbeing had deteriorated and the final third said that their mental wellbeing had stayed the same.

These numbers were staggering. Against a media backdrop warning of an emerging ‘pandemic’ of mental health difficulties, our findings highlighted that a substantial part of the young population believed their mental wellbeing had improved.

Because of the type of data we collected, we can’t say for certain what caused these perceived improvements, but we did notice some patterns. Compared with their peers, pupils who reported improved mental wellbeing were more likely to:

- report improved relationships with others,

- experience less bullying,

- manage school better, and

- get more sleep and exercise.

In sum, those who reported better mental wellbeing also experienced improvements across a wide range of social, educational, and health outcomes.

Lessons learned & a call to action

To me, these findings are a perfect example of a quote I once heard: ‘a lot is hidden in averages.’

In general, studies have focused on changes in the average levels of mental health during the pandemic. Many – though not all – of these studies found that mental health deteriorated. Of course, this is still cause for concern, and I am not for a moment suggesting that young people who experienced poorer mental health during the pandemic don’t deserve attention or support.

But what happens when you look below the surface of these averages? Our study revealed that there is a huge amount of diversity in terms of pandemic experiences. In other words, there was no one ‘typical’ experience for CYP and their families; rather, everyone has a unique story to tell.

So what now?

It may be easy to think that these findings are no longer relevant now that schools have re-opened, but I don’t think that’s the case at all. Lots of support has focused on those CYP who struggled during school closures (and rightfully so), but it seems as though few people have paid much attention to those who thrived.

Therefore, I challenge all those reading this blog – whether you are an educational psychologist, teacher, parent, or anyone else – to think deeply about the implications of these findings. Based on the numbers, every school will have some pupils who fared better during lockdown.

My challenge to you is to think about why that might be, but more importantly, how you might maintain some of the positive aspects of lockdown in the future. We all have an important opportunity – and even responsibility – to learn from CYP’s experiences of the pandemic to promote better mental health and wellbeing moving forward.

Further materials

- Read the original article by Emma and colleagues

- Read the press release ‘One in three young people say they felt happier during lockdown‘

- Watch Emma’s interview with Ontario’s news channel, CTV