Group process consultation: practice from the island of Ireland

Group consultation approaches have been a feature of Educational Psychology work for decades, with a wide variety of models and frameworks being applied (Muchenje & Kelly, 2021).

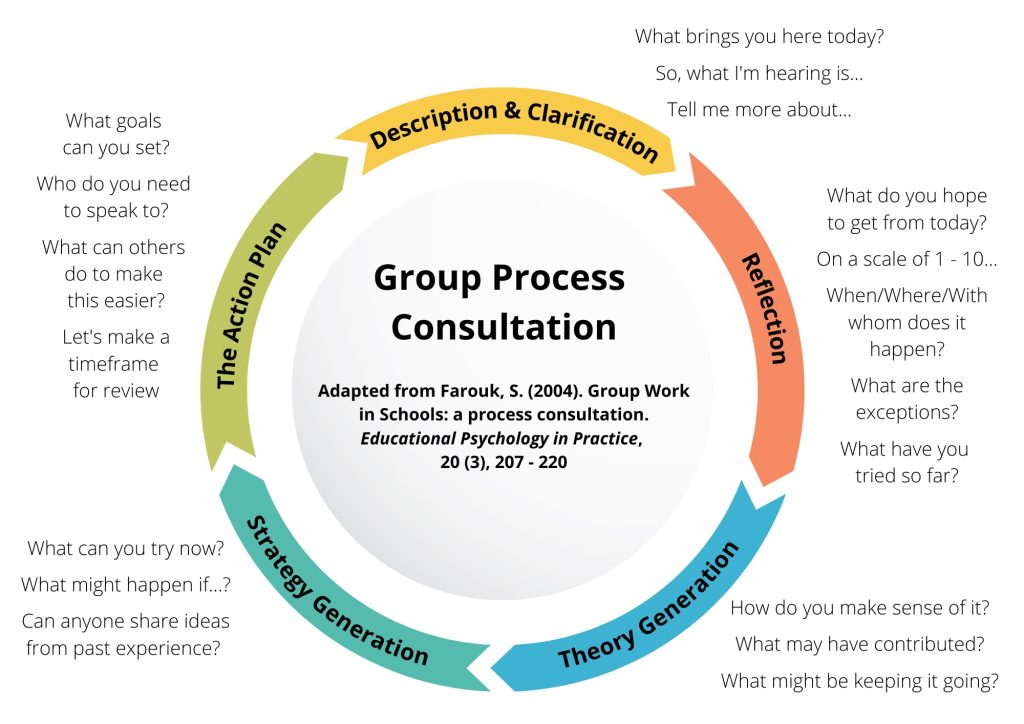

In this article, I’ll be outlining a form of process consultation used by EPs in Northern Ireland. This is based on a four-phase model proposed by Farouk (2004). It positions the EP as a facilitator consulting with a group of teachers about a particular concern. Some questions and prompts are provided in the following sections to give an idea of how the discussion evolves across the phases.

The Welcome

Each meeting starts with the facilitator thanking everyone for coming along and outlining the four phases. A co-facilitator is also introduced. Their job is to keep track of the time, take notes, and provide a summary of the themes discussed at the end of each phase.

Ground rules are also established. These include the ethos of listening and responding without judgement, encouraging everyone to share ideas and the use of pseudonyms or generic terminology to maintain confidentiality.

Phase 1: Description and Clarification

The referring teacher is given around five minutes to outline a concern. This first phase emphasises active listening, reflective commenting and paraphrasing what the teacher is saying. Other members of the group would only ask questions to seek further information or clarification.

- What brings you here today?

- So, what I’m hearing is that…

- Tell me a little more about…

- Are there any other issues which we need to clarify before we sum up?

Phase 2: Reflection

In this phase the group spend around fifteen minutes developing a richer understanding of the situation and digging deeper into specific details. The group is encouraged to ask questions, share similar experiences, and help the referring teacher to reflect on the context of the concern.

- On a scale of 1 – 10, where is the problem right now?

- What do you hope to get from this meeting?

- What needs to happen for this meeting to have been helpful for you?

- When/Where/With whom does it happen?

- When/Where/With whom does it happen less often?

- How do you feel when….?

- How do you cope with…?

- Tell us about the young person’s strengths/views/motivations/positive relationships.

- What have you tried so far?

Phase 3: Theory Generation

The group should now have lots of food for thought. The next ten minutes are spent on exploring theories about the concern. While the referring teacher may have their own views based on their knowledge and direct experience, other members can bring valuable insight from similar situations in their own practice.

- Has anyone an idea of what could be happening?

- Can we think of any pre-existing factors which might have contributed to this issue?

- What could be keeping the problem going over time?

- What is helping the problem to occur less often with certain times/places/people?

- Can we think of any protective factors? (Strengths, Interests, Resources and Supports)

- How do you make sense of the situation after hearing these theories?

Phase 4: Strategy Generation

Around ten minutes are allocated to the final phase, which considers potential ideas and strategies which can implemented by the referring teacher.

- Following on from the theories we discussed, what strategies can be developed?

- Can we think of ideas from similar experiences within the group?

- What do you think would happen if you…?

- How might they feel if…?

The Action Plan

The meeting concludes with five minutes of planning who is doing what, when they will do it, and the timeframe for review. The referring teacher and other staff within the school may have specific roles, while the rest of the group can signpost to relevant resources. The plan is disseminated to all members after the meeting, while the co-facilitator’s notes are destroyed.

- Which strategies can you try in the here-and-now?

- What goals can you set for the next few weeks?

- Who do you need to speak to? What can others to do to make this easier?

The process: a visual summary

The Follow-Up

A fifteen-minute meeting, around four to eight weeks after the initial consultation, considers the progress of the action plan. It maintains a solution-focused approach by eliciting the referring teacher’s views on what has worked well, what can be changed and any new actions to be taken.

- Returning to the scale of 1 – 10 from the last time we met, where is the issue now?

- What has gone well in the last x weeks?

- Which factors helped to achieve that success?

- Who else has noticed the change over time?

- Which strategies or plans have not worked as well?

- What needs to happen next?

How can this model of consultation be applied?

In Northern Ireland, the Farouk-based model was initially included in a multi-disciplinary approach provided by EPs and outreach officers from the local authority’s Behaviour Support Team. This offered school-based consultations about young people with social, emotional, and mental health needs. It incorporated solution-focused and motivational interviewing techniques (Duffy and Davison, 2009). The model has since been applied to Nurture Group clusters facilitated by EPs and the Nurturing Approaches in Schools Service. Teachers and teaching assistants from local Nurture Groups are invited to bring an issue for discussion.

The model can be flexibly applied to a range of contexts. The following are some examples of discussions which I have facilitated or co-facilitated in my own casework in recent years:

- Co-constructing a trauma-informed key adult role for a SENCO working with a care-experienced young person, who had recently begun to attend the school.

- Promoting the need to accept all forms of communication and identifying key relationships within school for a young person presenting with situational mutism.

- Considering theories about a presentation of emotionally-based school avoidance and devising strategies for making the school environment more welcoming and calming.

- Creating an action plan for various staff in supporting a young person at risk of suspension and expulsion. This explored current strategies which were successful and other ideas which could be trialled in specific circumstances.

What does the research say?

A two-year pilot project of the model was conducted with schools in Ireland. This reported positive feedback on the structure of the groups and the opportunity to meet with others and share expertise (Nugent et al, 2014). It was felt to be effective in establishing clusters of small rural schools. However, it was clear that initial training on the model influenced later satisfaction and it was felt to be an approach which needed to be grown over time.

Perceptions of the approach and factors which help or hinder its success were evaluated over the course of one year in three primary schools (Hayes and Stringer, 2016). This highlighted the importance of planning and organisation, ensuring that all group members had time to contribute and the readiness of schools to embrace the process. It was noted that the perception of the EP as the “expert” advice-giver, rather than a facilitator who encouraged the members to support each other, was resistant to change. While the study incorporated strong data triangulation, the lack of a comparison group and the reliance on questionnaires instead of interviews or focus groups were key limitations.

A mixed methods study by Davison and Duffy (2017) included teachers and teaching assistants from 11 nurture groups in Northern Ireland. Participants were provided with training on the model and engaged in six monthly consultations. The results indicated a decrease in the level of concern about the presenting problem brought to the meetings and positive change in teacher self-efficacy and the self-confidence of all participants. Several themes emerged, including the benefits of collaborative problem-solving, reducing stress, and building relationships within and between groups of staff.

There is a need for further research on the application of this group process consultation model, particularly the influence of competing agendas and differences in beliefs and values between staff at various levels of the school hierarchy. The impact on young people and parents/carers, and perhaps including them in a form of the process, is also worthy of consideration. For our profession, it represents a valuable avenue for joint working and peer supervision. Not only can EPs work together to facilitate meetings, but the model also provides a potential role and continuing professional development opportunities for Assistant EPs and Trainee EPs.

Chris can be found sharing practical tools and strategies on Twitter @DrChrisMooreEP, and blogging at EdPsychInsight

References

Davison, P. & Duffy, J. (2017). A model for personal and professional support for nurture group staff: to what extent can group process consultation be used as a resource to meet the challenges of running a nurture group? Educational Psychology in Practice, 33 (4), 387 – 405.

Duffy, J. & Davison, P. (2009). Incorporating Motivational Interviewing strategies into a Consultation Model for use within School-Based Behaviour Management Teams. In McNamara, E. (Ed). Motivational Interviewing: Theory, Practice and Applications with Children and Young People. Ainsdale: Positive Behaviour Management.

Farouk, S. (2004). Group Work in Schools: a process consultation. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20 (3), 207 – 220.

Hayes, M. & Stringer, P. (2016). Introducing Farouk’s process consultation group approach in Irish primary schools. Educational Psychology in Practice, 32 (2), 145 – 162.

Muchenje, F. & Kelly, C. (2021) How teachers benefit from problem-solving, circle, and consultation groups: a framework synthesis of current research. Educational Psychology in Practice, 37 (1), 94 – 112. Nugent, M., Jones, V., McElroy, D., Peelo, M., Thornton, T. & Tierney, T. (2014). Consulting with groups of teachers. Evaluation of a pilot project in Ireland. Educational Psychology in Practice, 30 (3), 255 – 271.